Dandy and Despot

22.05.2008

Süddeutsche Zeitung

back to selection

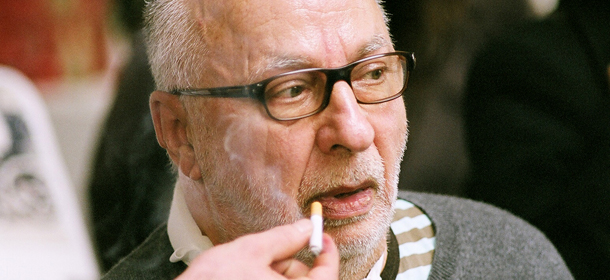

In her film I. Immendorff, Nicola Graef shows us the German painter-prince between cheerfulness and solitude

“The picture must take on the function of the potato!† The Immendorff slogan from his Café Deutschland, a cycle of 43 works produced between 1977 and 1983, brought him fame. Unimposing, serviceable, nourishing – do these traits not sum up the potato? But don't the artist’s exaggerated and spectacular gestures contradict this gospel of the potato? Then again, don't such contradictions make Immendorff what he is?

In the final chapter of her homage to Immenodorff, Nicola Graef observes a stirring scene, one towards which the entire film seems to be aimed: March 2007, two months before his death, in his studio, the artist presents his Gerhard Schröder portrait, which rounds out his gallery devoted to the office of the German Chancellorship. In attendance are photographers, VIPs, and the ex-chancellor himself. After the official ceremony, Immendorff is suddenly visible at the edge of the gathering. He sits alone in his wheelchair, breathing with difficulty. For 10 years, he has suffered from an untreatable disorder of the central nervous system (ALS), which has progressively paralyzed him. A respirator pumps air into his lungs jerkily, and it looks as though Immendorff is sobbing. Momentarily, a look of panic appears in his eyes. Then he tells of the inevitable loneliness and despair of the artist, feelings that go beyond his illness itself.

The film begins in 2005 with a scene in the studio. The master is occupied with preparations for the large-scale retrospective in Berlin's Nationalgalerie. We see Immendorff now as a strict, dictatorial boss who seems to be hiding his despair over his paralyzed hands behind a despotic attitude. An utterly different, almost cheerful atmosphere prevails when friends come to call. Archival footage casts brief spotlights on various life phases: the turbulent years of study with Joseph Beuys, the neo-Dadaist actions, the movement founded jointly with Dresden painter and “anarchist par excellence† A. R. Penck, and finally his brash entrance as a Porsche-driving party animal and friend of the German chancellor.

We should not hold it against this film that contrasts in Immendorff’s image (reverer of Mao, Reeperbahn dandy, art teacher at the Academy and highly-paid “painter sovereign†) are merely implied rather than vigorously portrayed. But the fact that no attempt is even made to penetrate into the work itself does become a decisive drawback. Nicola Graef uses Immendorff’s paintings only as motivic illustrations of his biography. But in fact, it is the biography that emerges from the work. Markus Lüpertz has formulated it as follows: “He had to be that which he painted.†

(Rainer Gansera)

back to selection